Feng Yan: Photography Objectified

Three Shadows Plus 3 Gallery, Beijing April 13–May 26, 2013

by Jonathan Goodman

|

|

Feng Yan is a mid-career, Beijing-based photographer whose work was shown this spring at Three Shadows Plus 3 Gallery, a commercial space located on the same grounds as the esteemed Three Shadows Photography Art Centre, in the Caochangdi arts district in Beijing (the former is affiliated with the latter but independent from it financially). The exhibition, primarily consisting of colour photographs of isolated everyday objects, brought up interesting questions pertaining to the social or domestic power of solitary objects and their effect on the viewer. Feng Yan’s sophistication, for example, in his colour rendering of the massive steps in The People’s Conference Hall (2006), emphasizes the monolithic nature of the depicted building but also instills an anxiety about its purpose, as the uninhabited stairs reveal nothing but themselves. And Feng Yan’s focus on another isolated object, as in Car Door (2006), an image of a detail of the sedan Joseph Stalin gave to Mao Zedong, is straightforward enough, yet a spirit of menace is communicated through the evidence of bullet hole indentations in the window. Even so, when looked at simply as an object, the car carries no particular meaning as a sign of political power; it is merely a picture of a car. But once one knows the car’s history, it loses its anonymity. His portraits of such things amount to a documentary-like treatment of myriad objects from everyday life within both the public and private realms.

|

|

Feng Yan, Car Door, 2006, C print, 85.7 x 130 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

Feng Yan’s imagery thus functions as a kind of mirror of the isolated object because he refuses to embellish anything in the photograph. The inclusion of Mao’s car photos, however, opens up questions about power given its ominous black paint, its massive solidity, and its provenance. This implies that the meaning embedded within this photograph is made powerful by the car’s politicized origins. So it happens that Car Door, like most of Feng Yan’s work, leans toward resisting interpretation until its context is made clear. This tends to position his imagery into the realm of the anonymous—at least at first look. |

|

Feng Yan, The People’s Conference Hall, 2006, digital photograph, 110 x 163.9 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

Of course, it is common knowledge today in contemporary photography that no image is objective, that the photograph reflects the photographer’s often subtle technical decisions and larger intentions. Yet a certain degree

of objectivity can in fact be achieved. For example, the unplugged electric fan depicted in Feng Yan’s Fan (2010) has specificity and functions as an object but it is so mundane that it is hard to imagine what personal meaning it might have for the artist. Its virtue as an artifact, however, lies in our ability to see something as it is, in all its detail, and without any cultural or even personal history. Feng Yan is attentive in presenting these objects as seemingly impersonal, even though most of them belong to the photographer himself. So, here, one doesn’t have to know the object’s origins in order to appreciate the distance between it, the photographer, and his audience. This effect of distancing amounts to a kind of alienation—as if the fan were somehow foreign and exotic—despite the utter familiarity we have with such an object. In these works of art, Feng Yan has attempted to absent the personal to the point where the items appear to have become cultural relics dug up from some contemporary midden, cleaned up, and carefully positioned for our close scrutiny.

But if Feng Yan is practicing a kind of cultural anthropology, he is oriented towards the physical materiality of the artifact rather than its cultural meaning. Moreover, this formal materialism shows us that objects are meant for use or public display rather than interpretation; material culture can be commented upon, of course, but the object’s real function is to do the job it was created to do. So Feng Yan’s documentation of the object places it in the realm of the ordinary to the point where the object assumes a banality. The fan is just a fan, although he has recorded it with notable precision. At the same time, the seeming objectivity his images present can have troubling connotations, as in the image of the bullet holes on the window of Mao’s sedan in Car Door or the staircase that appears to lead to nowhere. Moreover, Feng Yan’s work implies that the political is an inevitable part of cultural expressiveness. For example, focusing on something as seemingly trivial as a small group of bonsai plants that seem misplaced or trapped in a corner in Corner Plants (2006), enables Feng Yan to present his view on the present state of affairs in China. One can feel that current political conditions—China’s authoritarian rule—might here be alluded to, although such an interpretation is inferred rather than explicit. |

|

Feng Yan, Fan, 2010, digital photograph, 148 x 100 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

Still, objects have a life of their own. Even a simple photographic record of an object can have inevitable consequences, no matter how lacking in originality or personal attachment the object depicted may be. It is here that the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher can be cited; the German couple (Bernd Becher died in 2007) is internationally known for collaborative

studies of architectural typologies, of industrial buildings for example, mostly but not exclusively located in Germany. The Bechers’s images are completely without embellishment; indeed, the lack of it, and their promise of an undiluted objectification of their subject matter, accounts for the visual power of the structures they photograph. According to Feng Yan, he has only recently become familiar with the Bechers, yet there is a clear connection between his work and theirs. The tension between the artist’s subjective and objective states of mind, as illustrated in the Bechers’ impassive imagery, is also at the unspoken core of Feng Yan’s creativity. The inclination towards an industrial aesthetic in American Minimalism, in which the sculpture reveals no cultural narrative other than the conditions of its manufacture, is an approach not so distant from Feng Yan’s. Indeed, Feng Yan has remarked in conversation that he admires the Minimalist movement in general.

|

|

Feng Yan, Corner Plants, 2006, C print, 74 x 110 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

Yet, ironically, despite the politicized disposition of many of the sculptors who were affiliated with Minimalism, its style has become a favourite for corporate art—likely because of its very nihilism in regard to expressions of cultural meaning. Although Feng Yan’s photography could be understood as a sort of continuance of the New York Minimalist tradition, it is unlikely to hold aesthetic appeal within a corporate context. The artist himself spent time in New York, living in Williamsburg from 1998 through 2001, and here he would have had ample opportunities to visit galleries and museums, thus becoming knowledgeable about American art.

In a quite different sequence of images, titled Psychedelic Bamboo, also exhibited in this show, we encounter shots of neon tubes stacked on top of each other. In another reference to the Minimalists, and to an audience schooled in its accomplishments, these images might look like some sort of homage to Dan Flavin’s neon sculptures. Feng Yan is thus building a bridge not only between generations but also across a considerable geographic divide. The neon tubes emanate a central core of light; in Psychedelic Bamboo 10 (2009), a green band splits the middle of a composition that is otherwise dark aside from the minimal glow of green and red horizontal lines above and below. Feng Yan’s openness to Western aesthetics acknowledges the precedence of the evolution of modernist abstraction, but Chinese art jumped from socialist realism to a postmodern practice without engaging in a genuine late-modernist experience, so Feng Yan’s art is genuinely startling, seeming to have sprung fully formed into a postmodern context. One can also notice that as a title, Psychedelic Bamboo is an amalgam of Western hallucinogenic drug culture with a reference to

the ubiquity of bamboo in China, in both art and nature. Feng Yan’s use of abstraction also relates to his fondness for traditional Chinese painting with its dynamic nonrepresentational brushstrokes and flourishes.

|

|

Feng Yan, Psychedelic Bamboo 10, 2011, digital photograph, 120 x 90 cm. Courtesy of the artist |

|

The Psychedelic Bamboo series offers us both a contrast and an alternative to the highly documentary tendency that characterizes much of Feng Yan’s other work. The beauty within these images results from the internal luminescence of neon; in Psychedelic Bamboo 04 (2009), for example, the horizontal bars display a broad range of colours: blue, green, red, maroon, yellow. The muted glow of the colours gives

this image its power; it is reminiscent of works by other artists such as the aforementioned Dan Flavin, but it is also strikingly original. Indeed, the romanticism of these photographs—their deliberate beauty—raises useful questions about the relationship between photography and painting. For example, does the photograph continue to undermine painting’s ability for realistic representation? And why has current photography mostly been taken over by the conceptual artist and not by the realist craftsperson?

|

|

Feng Yan, Psychedelic Bamboo 04, 2009, digital photograph, 120 x 90 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

Even so, one recognizes at the outset that Psychedelic Bamboo 04 is indeed a photographic image, its narrow bands of colour self-evidently flat, lacking the more nuanced surface of painting; brushstrokes would add depth, however small, to the surface of the picture. In Psychedelic Bamboo 06 (2009) the bands are wider, and the edges between them blurred. The stripes are red and white in the top two-thirds of the image, while the bottom of the composition is much denser, consisting of dark maroon and dark purple, which shifts into a near black. These bands of colour are beautiful in and of themselves, but Feng Yan is do not deliberate in suggesting the act of painting. The flatness of the surface shows us that the image is resolutely photographic, even if it recalls, in its quiet luminosity, a painter like Rothko.

If the Psychedelic Bamboo series mimics painting to emphasize the fluid depth of photography in its presentation of objects, the series entitled The Monuments presents the object, as in so much of Feng Yan’s work, purely as a physical thing. This series, which, as earlier illustrated, depicts the artist’s own belongings, is utterly straightforward—again, much like the work of the Bechers—so that the bare facts of the object are revealed through its details. Feng Yan’s photographs of file cabinets, for example, taken in 2010, emphasize their intransigent existence as things, and are taken out of context by being isolated in a photographic image in order to emphasize their unadulterated specificity. He is asking his audience to see the photographed object in a new light, as if for the first time, and the result leads to full attention being paid to those ineluctable aspects that make the file cabinet so absolutely itself. Feng Yan’s realism, in this case, refuses to romanticize the object, although the cabinets show us the potential for a beauty that is nearly industrial. By remaining resolutely object-oriented, it is as if Feng Yan were reiterating, in a visual fashion, the truth of American modernist poet William Carlos Williams’ terse axiom: “No ideas but in things.”

|

|

Feng Yan, Psychedelic Bamboo 06, 2011, digital photograph, 120 x 90 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

|

Feng Yan, File Cabinet, 2010, digital photograph, 148 x 100 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

Yet these photos of objects, despite their rejection of idealization, derive a staying power based upon the elevation of detail within each one that is represented, demonstrating striking imagination on Feng Yan’s part. By emphasizing the object’s particular details, the artist focuses on the visual beauty found in their manufacture; it moves the viewer from its objective origins to a more expressive, beautiful image. And we can invest his facticity with a historically based awareness of art; for example, when looking at Black Stool (2010), Minimalism comes back into play with this work’s echo of the simple planks of the late American sculptor John McCracken that are painted one colour and stand against the white wall of the space they are in. Thus, although it is axiomatic that human truths are partial, there are degrees of truthfulness and impartiality that allow Feng Yan to present mere everyday objects as works of art. His Chest of Drawers (2010) roots the act of vision

in ontology, again emphasizing the physical presence of what is gazed upon. In his celebration of everyday objects, Feng proposes a less idealized, but equally eloquent point of view. This is because objects themselves possess an intrinsic value visually, no matter how small or ordinary that value may be.

|

|

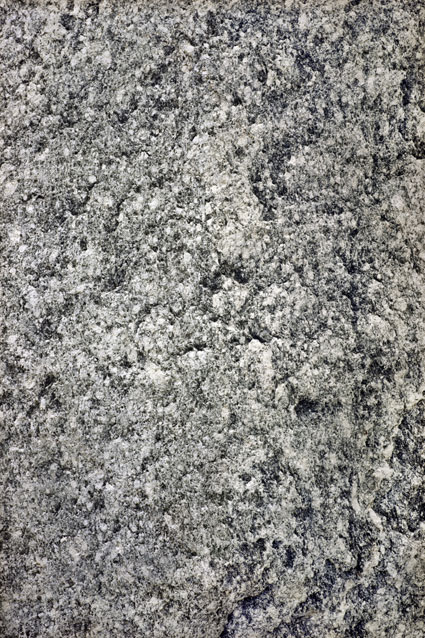

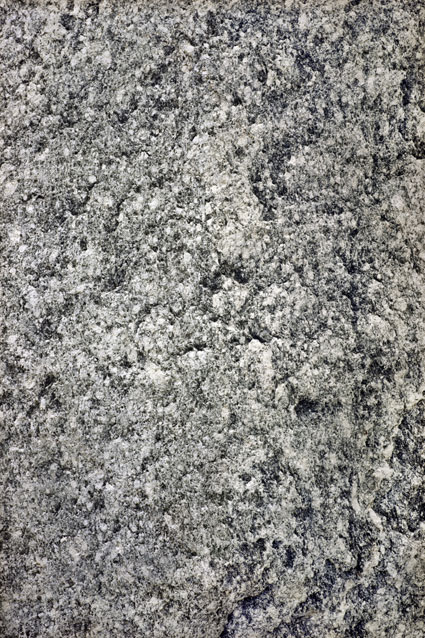

As the pictures described above do not specifically relate to Chinese culture, they could be considered international in outlook. Yet Feng Yan’s remarkable Rock series, also on view in the exhibition, fully recalls the tradition of scholar’ rocks portrayed in Chinese ink painting. His fine depictions of a rock turn their rough surfaces into objects of visual delight; Feng Yan turns back the clock by emphasizing the legacy of his culture. The large scale of the images—180 x 120 cm—makes them even more visually compelling. Even though one might relate this work to Chinese ink painting, the fact remains that Feng Yan continues his process of focusing fully on the object before him, finding a visual lyricism in it that is contemporary in its isolation of a particular object, and venerable in its recognition of tradition. Ironically, the pattern he finds in these close-ups, such as Rock 03 (2011), is suggestive of a Jackson Pollock drip painting, with a reference to Western art history again becoming evident. But in Rock 02 (2011), the affiliation is decidedly more toward Chinese ink paintings of mountains, proving that Feng Yan is not committed to any one style but, instead, to a process that results in subjects derived from a broad range of cultures and times. What ties this work together is an emphasis on extraordinary detail and clarity within each image.

|

|

Feng Yan, Black Stool, 2010, digital photograph, 148 x 100 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

Feng Yan, Chest of Drawers, 2010, digital photograph, 148 x 100 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

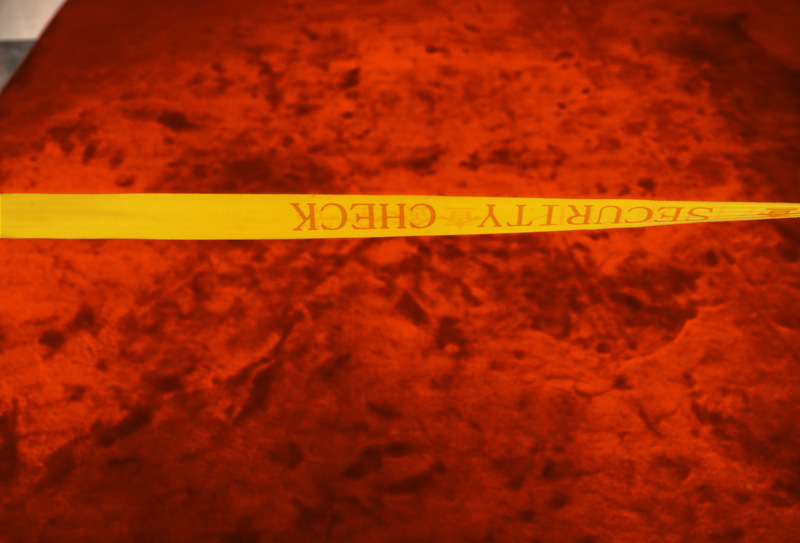

For artists, the current sociopolitical situation in China remains tenuous— the personal freedom of their lives can be compared to that in the West, but their freedom to express oppositional politics cannot. Part of the problem has to do with critical writing, of which there is very little to match that of the West (or so my Chinese artist colleagues tell me). Yet an artist can find subtle ways to suggest government control. Returning to the issue of power in Feng Yan’s work, in another stairway photograph, Military Museum (2006), the steps lead quite literally to a closed wall—as if access to the museum and its history is forbidden. Another work with political implications is Four Flags (2006), which consists of four red flags that lack the red stars that would make each the flag of China; it is as if the flag has had its national symbolism stripped away. The VIP Room (2005) looks ominous in its treatment of shrouded furniture and lack of people. And, finally, the plastic yellow strip whose red letters announce Security Check (2006) in front of an anonymous, red marble background, feels like a warning and conveys a sense of governmental constriction in everyday life.

|

|

Feng Yan, Rock 03, 2011, digital photograph, 180 x 120 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

Feng Yan, Rock 02, 2011, digital photograph, 180 x 120 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

|

Left: Feng Yan, Military Museum, 2006, C print, 141 x 230 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

Right: Feng Yan, Four Flags, 2006, C print, 148 x 230 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

| Feng Yan manages to merge opposites only to find them freed by the response and interpretation of his audience. Once his images are lodged in the viewer’s mind, the artwork can be interpreted in ways that may not reflect his intentions. But it is fair to say that the implicitly politicized images described in the paragraph above and grouped under the heading The Order—The Power, owe their effectiveness to the ambiguity with which they are presented by the artist. While there is nothing openly contentious about these images, gathered together they suggest a fragile resistance, one that cannot risk being more overt than it is. This is true for most artists in China; Ai Weiwei’s experience as an ethical witness of political decay is a cautionary tale. In China, art is taken seriously by the government and puts the artist in a place of dynamic morality. Feng Yan doesn’t talk about this sort of thing directly, either in life or in art, yet his concerns are such that they inevitably lead him to an independent stance. More artists like him are needed. |

|

|

Left: Feng Yan, VIP Room, 2005, C print, 110 x 164 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

Right: Feng Yan, Security Check, 2006, C print, 87 x 130 cm. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

|